Some use of AI in academic writing should be allowed without disclosure

Allowing the use of AI with a disclosure might seem like a straightforward solution to ensure integrity and transparency, but it is a bad policy

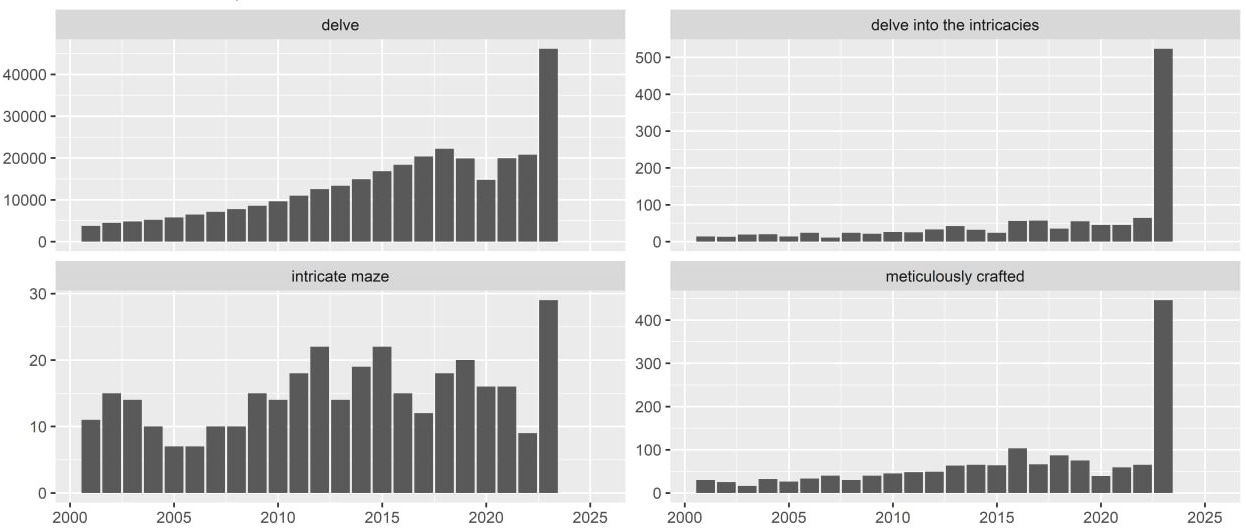

Last August, a Stanford student shared on Twitter the Google Scholar search results for the phrase 'As an AI language model’. This revealed that many scientific papers contained an apparently blindly copy-pasted output from ChatGPT. My colleagues recently published an analysis identifying more subtle markers of AI use, such as the spike in the frequency of the word 'delve'—one of ChatGPT's favourites—in scientific literature.

Understandably, such findings worry some academics who fear that we will be overwhelmed by a deluge of AI-generated nonsense. However, I do not share this concern. I don’t believe that any of my colleagues who are doing proper science would suddenly start copy-pasting ChatGPT output into their manuscripts without even re-reading it. I don’t think that reviewers who properly read the papers would suddenly be so blinded as to miss text clearly generated by AI. Proper scientists wouldn’t cite or even read such papers. These papers belong and will remain in a separate space of bad science that existed long before modern generative AI technologies.

Even before ChatGPT, there were papers with so-called ‘tortured phrases’ that appeared when unscrupulous “scientists” tried to evade plagiarism detection by automatically substituting synonyms. So ‘artificial intelligence’ became ‘counterfeit consciousness’ and ‘breast cancer’ became ‘bosom peril’. A computer-generated paper was accepted for publication as early as 2005. And nonsense was published long before that.

The existence of bad science is, of course, unfortunate, as these “scientists” often receive public funds and teach students. However, its impact on mainstream science is probably minimal. Bad papers may be as easily accessible via Google Scholar as proper scientific output, giving the illusion that they belong to the same domain. However, bad science exists in its own silo, and I don’t think there is strong evidence for its expansion since the release of ChatGPT. The scientists I know have not become more sloppy. If anything, they have become more cautious, as nobody wants to find themselves fooled by AI-generated work.

At the same time, Generative AI could have a significant positive impact on science by helping authors improve their academic writing, which—for better or worse—remains the main output of scientific work.

My previous post about Mannheim is a good example of the positive impact of GenAI, as it wouldn’t have been written without the help of ChatGPT. I didn’t ask ChatGPT to list the advantages of living in Mannheim. I don’t care what it has to say about that because I wanted to share my own experience. I didn’t ask it to expand a bullet-list draft into a full text because I wanted to tell my story in my own voice. However, I used it to proofread my text and improve my non-native English.

I don’t think it muted my voice by converting it to the generic empty smoothness of AI. In fact, it did the opposite. It helped me find my English voice. Writing is hard for me even in my native language. I often struggle with sentences that refuse to read smoothly. I could spend so much time on a single sentence without obvious progress that it entirely stalls my work. It also creates a psychological block, making me dread writing and procrastinate endlessly instead of starting or returning to a text. This is even harder in a non-native language. And writing personal texts is harder than professional writing, as I cannot stop thinking that nobody really cares about what I have to say.

The main advantage of ChatGPT is that it removes this writing block. I don't worry about awkward sentences anymore because I know I can always polish them with AI. Sometimes, I don’t even need to make adjustments in the end; it’s more of a psychological help. And when I do accept AI suggestions, I believe it makes the text better, helping me to express my ideas and feelings. This is really important to me. Communicating in Russian is no longer an option as I’ve lost contact with the Russian-speaking community. I don’t have the chance to meet new people in Sydney. So, this blog is a unique and precious channel for connecting with friends who are now on the opposite side of the world. Some of them even mentioned reading my previous post with interest, so this communication channel worked. And it wouldn’t be possible without ChatGPT.

If AI is embraced by the research community, it could empower so many researchers in their academic writing, just as it has helped me with my personal texts. This is particularly relevant since most scientists write in their non-native language. Interestingly, the main objectors to AI use seem to be native speakers. This should not be surprising, as the benefits for them are much lower, and they are, in fact, at risk of losing their privilege and advantage over other scientists.

The current position of most publishers is that the use of AI is allowed but should be disclosed. The Springer Nature policy is following:

Large Language Models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, do not currently satisfy our authorship criteria. Notably an attribution of authorship carries with it accountability for the work, which cannot be effectively applied to LLMs. Use of an LLM should be properly documented in the Methods section (and if a Methods section is not available, in a suitable alternative part) of the manuscript.

This is mirrored in the policy of the second largest publisher:

Therefore, AI tools must not be listed as an author. Authors must, however, acknowledge all sources and contributors included in their work. Where AI tools are used, such use must be acknowledged and documented appropriately.

And Elsevier’s policy is essentially the same:

Authors should disclose in their manuscript the use of AI and AI-assisted technologies and a statement will appear in the published work. Declaring the use of these technologies supports transparency and trust between authors, readers, reviewers, editors, and contributors and facilitates compliance with the terms of use of the relevant tool or technology.

Authors should not list AI and AI-assisted technologies as an author or co-author, nor cite AI as an author.

That might look like a sound policy: progressive enough to allow the use of AI but also insuring integrity and transparency by requiring disclosure. However, I think that forbidding the use of AI for proofreading and light editing without disclosure is a bad policy. There are several reasons for that.

First of all, it is ambiguous. What is AI, for example? While it might be clear that using a simple spell-checker is different from copy-pasting ChatGPT’s output, there is a whole spectrum between these extremes. I have seen policies, for example, where Grammarly is considered an AI technology and policies where it is viewed as a tool that does not require disclosure. Drawing a line becomes even more complicated as these technologies become seamlessly integrated into software that is already used for writing, like Microsoft Copilot in Word or TeXGPT in Overleaf. It is quite clear to me that Copilot and TexGPT are powered by the same technology as ChatGPT (it is even in the name of the latter!); however, I can imagine that this might not be evident to everyone. And this will only become less clear over time with more seamless and ubiquitous integration of AI in everyday life.

The ambiguity is closely related to another flaw of the policy: its arbitrariness. Practices that are now forbidden without disclosure were universally accepted—even if with other tools—without any concern. Human proofreading—which, in my view, should be more controversial than AI proofreading—was not only allowed but encouraged by publishers and never required disclosure. Some universities are apparently so scared of AI that they require disclosing practices equivalent to looking up a word in a dictionary:

Some might argue that all this grumbling is unnecessary since nothing is prohibited as long as a disclosure is provided. However, it is not even clear how to do this. Springer Nature absurdly suggests that it should be done in the Methods section, even though proofreading has nothing to do with methods. It is also commonly suggested that the entire input passed to a large language model should be disclosed. This assumes an unrealistic, straightforward scenario of AI use. Actual work with text involves numerous edits and rewrites. If AI assistance is used, a single paragraph might result from dozens of prompts. Sharing all this information would not only be impractical but also highly intrusive. Drafts and other details of the writing process have always been, and should remain, a private matter.

This essentially leaves just one option: to add a standard disclosure at the end of the paper, similar to those already being used:

This paper was proofread, edited, and refined with the assistance of OpenAI’s GPT-4 (Version as of January 5, 2024), complementing the human editorial process. The human author critically assessed and validated the content to maintain academic rigor. The author also assessed and addressed potential biases inherent in the AI-generated content. The final version of the paper is the sole responsibility of the human author.

My main concern with such disclosures is that they could affect how the paper is treated. I can easily imagine reviewers becoming more suspicious and biased towards such papers. I remember how my colleagues and I started to read student assignments differently since the release of ChatGPT. “Does this phrase sound too ChatGPT-ish to you?” we would ask each other. So, I wouldn’t even trust my own judgment. While I’m perfectly fine with people using ChatGPT for proofreading and light editing, I worry that if this is disclosed, I might become prejudiced towards the text. This would also create an unnecessary and potentially harmful division between those who use AI assistance and those who do not. The whole point is to empower scientists who were born outside English-speaking countries, not to mark them as second-class writers.

It might be that there is no bias and such disclosures won’t affect the perception of a paper at all. But if it doesn’t affect anything, then what is the point of requiring it?1

This blog post is written in my personal capacity. The opinions expressed are solely my own and do not reflect the views or policies of my employer.

Please note that AI can, of course, be misused. I have seen a clear AI hallucination in a text presented by someone as their own work. However, such issues are irrelevant to the use I’m describing here and already covered by existing policies anyway. For instance, it has never been acceptable to copy-paste text without indicating it as a quote. The same obviously applies to text generated by ChatGPT from scratch. It has also never been acceptable to use random internet posts as valid references, and the same holds true for ChatGPT output. To be honest, I am a bit confused when such cases are presented as new problems caused by AI that require new rules

I can't agree more. The policies of required disclosure are intrusive and inherently discriminatory, not to mention utterly impractical. They aare embarassing to the publishers, because they are based on fundamental misunderstanding of the many ways in which humans interact with AI. Nothing but the quality of the output shuold be used as a criterion to accept or reject a publication.